Art is the most wonderful passport to making friends around the world. Sharing, learning, agreeing, disagreeing - friendships flourish and deepen over time. Many a time, art has been the bridge to making that friendship, just as it has down the ages for so many people.

Read MorePrehistoric Art

Links with Past Artists /

Every time that new findings are published about art found on the walls of caves, it seems that our links with artist ancestors get pushed back further and further in time. In other words, artists have been among the earliest hominoids to be able to organise abstract thought and find ways to express themselves visually. The remarkable announcement, about three days ago, that an Australian-Indonesian team has dated the ghostly outlines of human hands on the walls of Maros Cave, on the island of Sulawesi, to 39,900 years ago, has electrified everyone. Not only is this one of the oldest examples of a form of art (created by blowing pigment dust onto outstretched hands to create the negative outline), but it is the first proof that Europeans were not the only early artists. Asia had its share of them too. And most likely, given time and luck, examples of this early rupestrian art will be found in Africa too.

Nonetheless, despite the dating of these hand outlines by sampling minute layers of the minerals covering them and using the radioactive uranium in some of them to fix this date of 39,900 years, there is another earlier artistic site. In the Panel of Hands in the El Castillo cave in northern Spain, a red dot amongst the hand outlines has been dated to more than 40,600 years ago.

Not so long ago, at the beginning of September this year, there was another fascinating announcement, more controversial, but nonetheless pretty persuasive. In Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, an abstract, almost hash-tag shaped rock engraving has been dated to about 39-40,000 years ago, but has been ascribed to Neanderthal artists. Just like their modern descendents, those far-away artists were capable of creating different types of art, whatever the purpose may have been. Again, this is not the oldest rock engraving - that distinction can be claimed by a 54,000 year old engraved sliver of rock found at the important archeological site, Quneltra, in the Golan Heights, Israel.

These early traces of artistic endeavour keep turning up, making for mind-stretching connections if one is an artist. It is such a fascinating link. Why did those early artists create their images of hand outlines, of amazing animals (like the strange pig-deer, the babirusa, from Sulawesi), of deeply incised lines in obdurate rock? Why, too, did the artist depicting this babirusa exaggerate the animal's different proportions and, even more rare, place it on a ground surface instead of having it float on the wall as was usually done?

If these artists were driven by the need to invoke spirits of their vital food sources, or signals to fellow inhabitants, or claim shelters, or whatever, they still had to get into deep, dark caves and have enough artificial light (fires, flares - flickering and fugitive) to see. They also had to take in with them the pigments and tools to create the art. They had to have the mental ability to conceive how to translate their ideas into art. That included a wonderful imagination about how to use the different characteristics and configurations of the cave walls and ceilings to the best advantage for their artistic purpose.

In other words, they are no different from every artist today, in the 21st century. We all have to conceive of what to say in our art, how to do it, how best to get it seen by others, and - if we be so lucky - get it seen by our descendents millennia hence!

Boulders, Works of Art or Something More Important? /

Reading an article by Stephen Knudsen in April-May’s edition of Professional Magazine entitled ”To see a Work of Art” made me think back to a recent experience I had in Portugal. Knudsen’s article was about spending a day at the Los Angeles Museum of Art to see sculptor Michael Heizer’s LevitatedMass.

Steve Knudsen first explained about the controversy surrounding the granite boulder’s final installation at the Museum in 2012 after Heizer first sketched out the idea back in 1969.Then Knudsen described the rewards of sitting watching this enormous boulder suspended over a ramp, ranging from the reactions of fellow visitors of all ages to the final crescendo at sunset of the boulder seeming to rise as the sun sank. He comments that “the seemingly grand narrative of moving the rock was, in the end, just a blip in the bigger story that points to sublime space, celestial movement and geologic time” (my thanks to him for this quote).

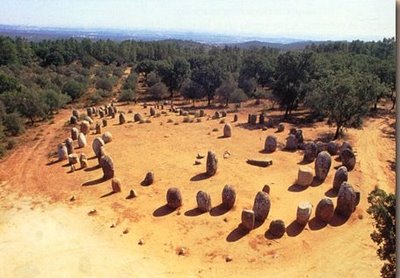

His remarks took me straight back to my amazing hours in early March at the Cromlech dos Almendres, near Evora in Portugal. One of the most important megalithic complexes in Europe, it is sited on a gentle hillside, overlooking rolling hills towards Evora, amidst olives and cork oaks. Daring from the 6th millenium BC, this extraordinarily grandiose ensemble of roughly one hundred boulders takes one's breath away as you approach the wide-flung site.

Just as Michael Heizer must have thought long and hard about his boulder, its shape, its material, its potential home and how it would best be viewed there, its messages and meaning to anyone viewing it – even how to transport it to the site, so too, our ancestors must have spent much time planning the Cromlech dos Almendres.

Like Heizer’s boulder, the huge megalith boulders are granite. Wonderful shapes, some of these monoliths have some carving on them, now well worn, but still hugely evocative as the sun moves and catches different angles and shapes on their surfaces.

Apparently these boulders were placed at different times, in concentric circles and later ellipses, all on a southeast-northwest axis. The entire group occupies an area of about 70 by 40 meters. Many of these massive stones are three meters high, while others, of earlier date, are slightly smaller.

Just to transport them to this hillside must have required incredible effort and organization, let along to site them and erect them into a vertical position. The endeavour speaks of enormous religious and social fervor, amongst groups of people who were few in number to start with. Connections with the land, their gods perhaps, their social structures – this was a huge undertaking to assemble these wonderfully powerful and eloquent boulders. Perhaps too the ensemble of monoliths was used for astronomical purposes.

Whether artistic considerations came into their choices of the stones to transport and place – who knows. But the carvings, whatever their significance, are beautiful too, and the carvers must have been conscious of that aspect. Many of the stones are flatter on one face, perhaps shaped deliberately. Each boulder speaks, as the sun moves around it and it relates to the next boulder and then the one beyond. The tactile qualities of the granite, so enduring, so interesting as the lichens hint at the northern side of the boulder, are memorable.

Like Stephen Knudsen’s perceptions of Levitated Mass at LACMA, the impressions that the Cromlech dos Almendres leave with one are of grandiose endeavours. Eight thousand years ago, men and women believed deeply enough in matters beyond their daily needs, in matters that transcended space, time and the span of human life, to expend enormous physical effort to create a sacred place of power and great beauty, sited exquisitely, laid out with care and sensitivity for the natural flow of life.

Even in our complex technology-driven 21st century, a visitor to the Cromlech is awed and inspired by the powerful voices that speak to us from the past of older, deeper, more important matters.

25,000 years - What a Heritage as an Artist! /

Visiting Pech-Merle Cave in France has been on my wish list for a long time, and this week, I achieved the wish.

What an amazing place and what a heritage we artists have in these cave drawings that early man created on the rock walls!

Location Map of Pech-Merle Cave, France

There is an astonishing mixture of the most beautiful stalagmites in columns, fans and banks with these seemingly smooth rock faces where those distant artists left their marks.

Enormous chambers, still dripping with moisture and forming more beauty in the limestone, have a sense of the spiritual, despite the fact that visitors are in groups, shepherded along by a guide.

Pech-Merle Cave

There is almost too much to see and absorb, too many shapes and formations to encompass; one longs to be able to slow down and linger. Alas, that is impossible because there is a limit of 700 visitors a day to try and conserve the freshness of the art work.

The cave was blocked by rock falls for many thousands of years, which helped conserve the drawings better than in other caves. Thus there is the obvious concern to keep them in a good state of conservation.

Those early, few artists were determined people. It is hard to imagine the effort it must have required before they even traced the first line on a rock face. Cro-Magnon man lived in the fertile Lot river valley far below. There, the artist must have first had to prepare charcoal in stick form or grind red ochre into powder, fine enough to be blown through a small tube. Then he (judging from the content of the Pech-Merle drawings, it had to be a “he”!) had to climb up the steep hills to gain entrance to the cave. Before scrambling into the cave down narrow, tortuous openings, he had to ensure he had enough, reliable light from his flickering, open flame torches. Then, once inside the chambers, he had to select a rock face he could reach, that was not too damp and that lent itself to the images he planned to draw.

Even the rock surface was rough, not an easy surface for mark-making. One of the remarkable aspects of cave art is that there are layers upon layers of work. Art was executed on the same surface with thousands and thousands of years in between. In Pech-Merle, the first frieze of black drawings – bison, mammoths, horses of extraordinary vigour and freedom, probably all done by the same artist – has red iron oxide dotted markings beneath that are thought to be done some 8000 years previously.

Early Blown Pigment Hand Outline, Pech-Merle Cave

Mammoths and Horses - Black Frieze, Pech-Merle Cave

Young Mammoth, detail of Plack Frieze, Pech-Merle

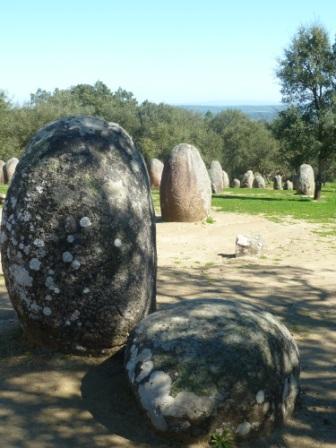

The most famous of Pech-Merle’s rock paintings, the Dotted Horse Panel, is vast and breath-taking. I was lucky enough to happen on it a few minutes before the rest of our group, and being alone to contemplate this extraordinary complex work allowed a dazzling connection with those long-ago artists.

Dotted Horse Panel, Pech-Merle Cave

Hand outlined by blown pigment, detail of Dotted Horse Panel, Pech-Merle

There was an early, early depiction of a long, spotted fish in red ochre, half obscured by the later drawings of the horses. The artist who conceived of and drew the horses used the configuration of the rocks themselves to incorporate them into the drawing. The outline of the rock suggests the horse’s head and neck, and the drawings flow from there. All the marks were blown stencils of fingers, thumbs and hands – all used to further the depiction of these two stylized horses with their powerful bodies and diminutive legs with dots big and small. The work bespoke of a clarity of vision and execution that would defy most people today with far, far better working conditions. Remember, flaming torches only have a finite time to burn, for example.

What also fascinated me in Pech-Merle was that those early, early artists not only celebrated the animals of their world, but they also made abstract drawings – triangles, strange symbols… - as well as very stylized depictions of women, even bison-women.There is also a poignant stylized man, lying mortally wounded with spears traversing his body, near a geometrical symbol.Interestingly, it is thought that artist travelled some 40 kilometers to another cave to draw the same type of wounded man, with a similar symbol, but not directly adjacent to the man as it is in Pech-Merle.

Wounded Man and Geometral Sign, Pech-Merle Cave

I suspect that every visitor to Pech-Merle emerges into the light of day dazzled and enthralled.

The mind-stretching sense of time and connectedness to those astonishing artists left me humbled and yet almost exalted at the thought of the heritage we artists share with those mark-makers working some 25,000 years ago.

Drawing - a High-wire Act /

Lorne Coutts is a frequently quoted advocate of drawing. One of his statements that resonates the most - understandably - is: "Drawing is risk. If risk is eliminated at any stage of the act, it is no longer drawing." (Trying to find out more about Lorne Coutts leads one to mysteries - borne in 1933, he has apparently published one book, in 1995. Entitled The Naked Drawings, it is out-of-print, with "image unavailable" on almost every listing - what a surprise!

In any case, everyone who has ever launched into drawing, especially without the psychological support of an eraser, knows that the results are a gamble. Even the most skilled of draughtsmen will have a surprise sometimes, a huge success but also, potentially, a total disaster. Just as the thoughts we think and the words we utter sometimes surprise, delight or dismay us, so too the lines that we place on a drawing surface can be a high-wire affair.

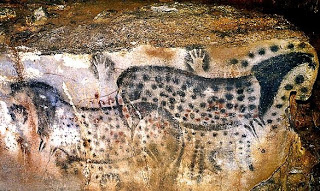

Even the very first lines made on the rock faces of caves such as Lascaux, France, showed that those artists, working some 40,000 years ago, were not only daring in concept and mastery of line, but they combined these aspects with the understanding of how to use the protuberances of the rocks to add extra impact to their drawings.

Lascaux

Think of the amazing kaleidoscope of drawings, often very gestural, that show how the artist is combining eye-brain-body/hand coordination and skill to produce a series of marks on a surface. Western art is rich in such drawings, as is Eastern art. Think of Leonardo da Vinci's work in chalks, for instance, or go to the other side of the world, to Japan, for drawing with brush and ink.

Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for the Heads of Two Soldiers in the Battle of Anghiari (1504-05). Image courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Sekkan (active 1555-1558) Monk Riding Backward on an Ox. Hanging scroll; ink on paper Image: 13 7/8 x 16 7/8 in. The Phil Berg Collection. Image courtesy of Museum Associates/LACMA

A little earlier, about 1510-15, back in Venice, Titian's searching chalks were recording this sensuous, thoughtful Young Woman, the lines probing and balancing - a deeply intense study.

Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian (Italian, ca. 1485/90-1576). Study of a Young Woman (detail), ca. 1510. Black and white chalk on faded blue paper. 41.9 x 26.5 cm (whole drawing).

© Prints and Drawings Department, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

There were so many extraordinary master draughtsmen during that period, from the Renaissance onwards, who could create fireworks and pirouettes of drawings - Michelangelo, Raphael, the Caracci brothers, Mantegna, Dürer, Caravaggio, Rubens, Tintoretto, and many, many others. One of the 17th century giants was of course Rembrandt. Just look at Rembrandt van Rijn's quick drawing of the two adults with the serious little child, or his flying strokes as he depicted this amazing lion.

Two women teaching a child to walk, Rembrandt, 1635-37. Red chalk. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Extinct Cape Lion, Panthera leo melanochaitus, Rembrandt, 1650-52. Ink. Image courtesy of the Musee du Louvre

Jumping to the late 19th/ 20th century, the high-wire act still goes on for some artists who draw, draw and draw. Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele are two Viennese artists famed for their drawings.

Egon Schiele, Crouching Woman, 1918

Another amazing draughtswoman working in Germany about the same time was Käthe Kollwitz. Constantly risking, constantly probing, she recorded human suffering and disasters in a way that rivets and remains in one's memory long afterwards.

K. Kollwitz, Self Portrait

Even during the later 20th century when drawing skills were less appreciated, there were artist who persisted in working on the drawing trapezes. One of the high-flyers was Lucien Freud, who produced powerful, direct drawings, mostly of people, and sometimes his dogs.

Arnold Abraham Goodman, Baron Goodman by Lucian Freud, charcoal, 1985, 13 in. x 10 1/2 in. (330 mm x 267 mm), Given by Connectus Komonia Trust, 1986, Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

So many artists who dare to draw. They inspire the rest of us to aim for the high wires, even if the drawing only succeeds once in a while. But the more one draws, the more it becomes part of one's psyche. After all, as Keith Haring observed, "drawing is basically the same as it has been since prehistoric times. It brings together man and the world. It lives through magic."

Art - Binding People Together /

One of the most fascinating books I have recently read is Eric R. Kandel's newly published book, "The Age of Insight. The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind and Brain. FromVienna 1900 to the Present". It is dense, interesting and challenging, as it details the many new discoveries of how the brain works and the many dimensions of humankind's involvement with art over millennia. There are so many aspects of the book that are worth talking about, but one short passage resonated with me because of my recent visit to South Italy, a place so rich in history.

In a chapter entitled "Artistic Universals and the Austrian Expressionists", Kandel delves into the large questions as to whether art has "universal functions and features" (p. 440). He goes on to state that, "Since the artist's creation of art and the viewer's response to art are products of brain function, one of the most fascinating challenges for the new science of mind lies in the nature of art." The questions then multiply: do we respond to art because our biology dictates our reactions, do we respond to art instead as individuals with our own personal experience and taste? Kandel refers to one opinion formed by Dennis Dutton, a philosopher of art, that art is not simply "a by-product of evolution, but rather an evolutionary adaption - a instinctive trait - that helps us survive because it is crucial to our well-being." (my emphasis)

Kandel goes on to allude to Cro-Magnon man painting those marvellous images in the Grotte Chauvet, 33,000 years ago, and reminds us that apparently, the Neanderthals, also living in Europe during that same period, did not create representational art. The conclusion which experts, such as social psychologist Ellen Dissanayake and art theorist Nancy Aiken, have reached is that art was a crucial means of binding people together during the Paleolithic age. People gathered together in communities and thus enhanced their likelihood of survival; one way to create this social glue was to make objects, images, and events that were important to these people, memorable and pleasurable. Just like the festivals celebrated all summer in Southern European towns and villages today, despite economic gloom; people enjoy themselves and reinvigorate their social ties, enhancing their daily life with religious or ceremonial events.

I immediately remembered two humble, but to me very powerful, objects I had seen and drawn quickly in the Matera Archaeological Museum in South Italy.

Upper Paleolithic stones from Matera area, South Italy, Prismacolor, Jeannine Cook artist

Hasty drawings, but what fascinated me was the literal binding-together marks that were on these stones, of a shape and size that would fit comfortably into a human hand. Just my interpretation of the marks, but I found them compelling. Even then, so many thousands of years ago, for the Upper Paleolithic age officially lasts from 45,000 to 10,000 years ago, our ancestors were scoring careful, thoughtful marks into stone, driven by a need to create art, art to bind those communities together most likely.

The fact that those stones can still compel our attention today makes an even stronger case for art's universal power to bind humans together.

Connections to the Earth through Art /

Sometimes life brings those wonderful connections and coincidences together to make a point in the art world, at least for me.

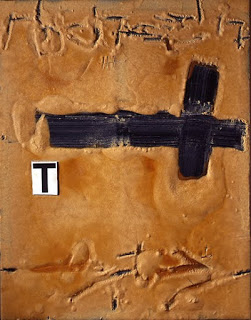

Last Tuesday, 7th February, the papers were full of news of the death of the great Spanish painter, Antoni Tapies, at the age of 88. I had always associated his work with the highly imaginative and almost mystical use of all kinds of materials, from clay, marble, sand and earth to cloth, always with an evocation of man's passage through life, with its pain and experiences that were grounded in his Spanish world. I remember being riveted by his use of ochers and other clays in a passionate series of canvases that were exhibited in Mallorca a long time ago.

As was reported in an article in The Nation, in 2004, Tapies spoke about his interest in "deeper, more serious colours" partly because he wanted to "feel close to the earth." "I have always wanted to get closer to the formations of the universe. Deep down, we are made of earth – and we go back to her."

Black I, mixed media, 2007, Image courtesy of Waddington Galleries, London

Tapies at his most tactile and Zen-like.

Then comes the coincidence that I loved: in a February 8th, Wednesday, Diario de Mallorca newspaper, there is a small item of news that forms a wonderful linking circle for me.

The famous Nerja Caves, in Andalucia, Spain, has a wealth of Paleolithic rock paintings dating for the most part between 16,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Rupestrian Art, Nerja Caves, Andalucia

However, it has just been ascertained that six of the rock paintings possibly date from 42,000 years ago, thus placing them amongst the first works of art created by man. Even more interesting is the hypothesis that Neanderthals created these rock paintings, not Homo sapiens. Quite a thought!

So a 20th century Spanish artist working for the most part in Cataluna, just up the east coast of Spain from the Nerja Caves, is hailed for his use of clay and other earths, and his deeply-held beliefs about humankind's mystical bonds with the earth. A few hundred miles and possibly about 42,000 years after early versions of mankind were virtually creating the same kind of mystical marking with the same clay materials. It certainly gives one a sense of perspective about what it is to be an artist.

More about Self-portraits /

When I was writing recently about art being a form of self-portrait, a record of where each artist is in time and space and outlook in life, I remembered another statement, this time by Leonardo daVinci. He said, "Every painter paints himself. Painters seem to paint their own faces and make paintings that seem directly involved with their own life. " Indeed, there has been much speculation about many of Leonardo's portraits using his own features, such as this video of Siegfried Woldhek talking about his search for Leonardo's self-portraits. This image is the most famed, done between 1512-15 in red chalk, when Leonardo was in his sixties, a drawing in the Royal Library of Turin.

Self-Portrait, Leonardo da Vinci, 1512-15 in red chalk drawing (Image courtesy of the Royal Library of Turin)

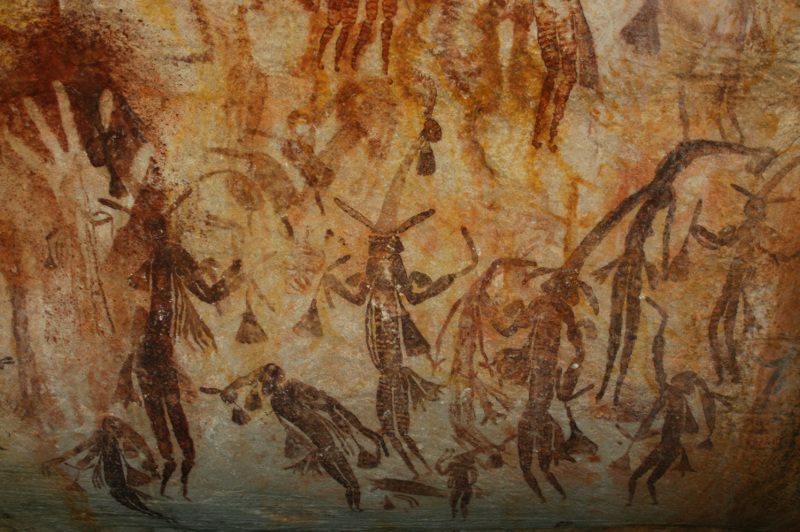

The urge to record one's own existence, one's presence, has been with us humans since time immemorial. This form of saying "I exist, I am present", in visual fashion, is testimony to mankind's sense of community, of shared characteristics that are more important than their differences, at least at some moments in our history. One of the most amazing collections of human representations is apparently becoming better known and understood in recent years - the GwionGwion rock paintings in the Kimberly area in N.W. Australia. Not only are these rock paintings probably more than 40,000 years old, but they tell of human life and adventures in stunning, elegant fashion.

Tassel Bradshaw (Gwion Gwion) figures wearing ornate costumes

Bradshaw figure, ( courtesy of the Bradshaw Foundation).

As examples of artwork that reveals the artist's own experience, in "self-portraiture" style, there is a red rock painting of a boat, the earliest known in history, that tells of man's migration to Australia via a four-man canoe on the Gwion Gwion rocks.

Bradshaw boat people, 40,000 years ago

There is also another long panorama of four-legged, antlered animals that the artist had evidently seen during the migration from SE Asia. There are no such animals, now or in early times, in Australia.

Gwion Gwion (Bradshaw) paintings on a rock wall.

Gwion Gwion cave paintings in the Kimberely

This huge collection of rock paintings, in hostile, difficult and remote terrain is an astounding example of man recording existence, beliefs, and ceremonies from very early times that one author, Jo Lennan, describes as "a forgotten Eden". The name, Gwion Gwion, comes from a bird's name. The Aboriginal people recount that this bird pecked the rock with such force that its blood sprang forth and it used its bloodied beak and feather to delineate the elegant, dainty figures. Indeed, it is thought by today's experts that these long-ago artists actually used quills to make the fine lines on the rocks. The actual dates of these early artists' work are still being determined, because the pigments used to draw have become part of the rocks themselves, and carbon dating doesn't work, especially in the tropics where its limits of dating go back +-40,000 years. Nonetheless, apparently on top of one drawing, there is a fossilised mud wasp's nest, and optical luminescence (which dates when something last saw the light of the sun) allowed a date of about 17,500 years for the drawing. This means that these artists were telling of themselves and their world at the same time as their long-distant colleagues were painting the wonderful images of their immediate universe on the cave walls in Lascaux, France.

What marvels we all inherit when such artists create "self-portraits" of their personal worlds.

Art as Witness for Ourselves as Humans /

A well-respected and prolific Spanish writer, poet and essayist, Felix de Azua, has just published an Autobiography without Life or Autobiografica sin vida (Mondadori 2010) which sounds fascinating and thought-provoking.

Starting with the book cover which uses an image from the 30,000 year-old drawings of horses found in the Chauvet Caves in France, he traces his own life, that of his generation and, in a wider sense, that of western art in general by images of artwork down the ages. His thesis is that the art we humans create bears witness for us as human beings. For century after century, representative art has reflected our place in the world, showing what surrounds us, and what matters to us. At the same time, that art also acts as a substitution for the reality depicted.

For the people frequenting such caves as Chauvet, Lascaux or Altamira, the magic of the rock face art was potent. Its power still reaches us. (As a confirmation of this, I read this week that the Spanish authorities have decided, despite the chorus of opposition from the scientific community, to reopen the Altamira caves to public visits.)

Rupestrian Art, Altamira Caves, Spain

Chauvet Cave Art Paintings (Image courtesy of Bradshaw Foundation)

But over the generations, Felix de Azua contends, this magic has been diluted, dissipated, stolen from art - he cites David's Marat, Goya's Disasters or even Rothko's work as having converted art's magical qualities into shadows and undiluted (maybe soulless?) representation culminating in today's performance art. In Azua's opinion, the nuclear bomb unleashed at Hiroshima not only proved to all mankind that our species is capable of total self-destruction, but it also caused a huge rift in the history of art.

Azua feels that we are thus in the early days of a totally new era in art, one that is full of complexities, given man's awareness of his own potential disappearance. Our awareness of the nuclear threat may be only subliminal now, but the threat does influence today's forms of art. Nonetheless, the magic inherent in art-making still exists or can exist. This "communion with the cosmos" is still necessary for us as humans, in art, in literature, in falling in love. As Azua remarks, "I also know that we cannot do without art, just as we cannot do without religion or science."